Lycoming Engine Maintenance - Some Dos and Don’ts

Brian Costello – Lycoming Engines | Contributing Author

When was the last time a helicopter owner or operator walked into a hangar with a question about an engine or aircraft that was not quite right, talked to a helicopter maintenance professional and walked away without at least a couple of ideas on how to fix it? In my 25 years of aviation experience, I can’t remember a single time. This strong desire to help others is the reason Lycoming agreed to put together a list of helicopter engine “dos and don’ts” for this issue of HeliMx magazine.

From the start, I knew I would have enough material to keep up interest. The problem was narrowing the material down to the “critical few” that apply to most situations and positively impact the majority of helicopters.

I can also lean on my 14 years on the front lines as a field service engineer for Lycoming Engines. Whether through my everyday work duties or special events like technical presentations at trade shows such as Helicopter Association International (HAI), I have been able to connect thousands of users with the collective expertise of a company that has been designing, manufacturing, testing and troubleshooting engines for the aviation marketplace for more than 80 years.

Service Bulletins, Instructions and Letters

By far the most important “do” I can tell you is to read and follow our library of service bulletins, service instructions and service letters, the latest of which are available at www.lycoming.com. They will provide you with the latest necessary information you need to do your job. They are also a safety net for you, the helicopter maintenance professional, and the people who put their trust in you. Study them and stick to them and everyone will benefit.

The Wobble Check

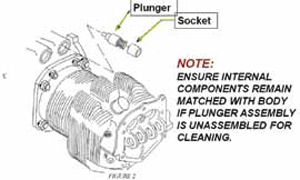

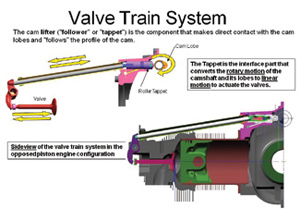

Do the complete procedure called for in service bulletin 388C. In order to do the procedure properly, you must disassemble the entire valve train and the hydraulic plunger must be removed. Remember to identify everything so you can return it to the exact location from which it was removed when you are finished.

Don’t take shortcuts. A common shortcut is simply to compress the hydraulic adjuster without removing it and cleaning out the oil. However, that could lead to a misalignment of the adapter cup, which is not visible and which goes between the plunger and the pushrod. Rotate the crankshaft with a misaligned adapter cup and you can cause damage even before you start the engine. Another “don’t:” do not expose the hydraulic plunger to magnetism. Doing so will prevent it from operating properly in the future. That is what we commonly refer to as a $75 mistake. Finally, do check the dry tappet clearance when the valve train is reassembled. If adjustments are needed, change the pushrod(s) per SI 1060K.

The Oil Change

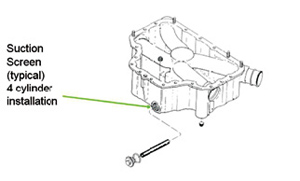

Do a visual inspection of the oil suction screen every oil change as required by service bulletin 480E.

Don’t substitute spectrographic oil analysis for a direct visual inspection of the oil filter and the suction screen. The suction screen is hidden and easily overlooked. That’s no reason to ignore it, as it could provide valuable clues to how the engine is operating in many places you can’t easily see. While Lycoming recommends spectrographic oil analysis, that analysis does not replace the required visual inspection.

Basic Engine Compression Inspection

Do perform the engine compression test with the engine “hot” as defined in service instruction 1191. That means operate the engine until normal cylinder head and oil temperatures are attained; then shut down the engine, making sure that the magneto switches and fuel supply valves are shut off. Proceed with the test as soon as possible after shut down. If any of the cylinders are between 10 and 15 psi off, test them again after 10 hours of operation.

Don’t take shortcuts and don’t ignore either the warm-up or the 10-hour recheck. We’re all busy and, in this case, the cold engine shortcut might give you a chance to move on to another job quickly. However, you may end up costing the price of a new cylinder you failed to inspect properly. More importantly, done correctly, the compression check may keep the helicopter safe because you identified the compression problem accurately. A final note: you don’t have to pull the cylinder if the compression is off by less than 15 psi. Often during the 10-hour operating period, valves reseat themselves and compression improves to acceptable levels.

Rough Running Fuel Injected Engine

Do check and clean all fuel nozzles, fuel screens and/or filters first before proceeding further when investigating a rough-running fuel injected engine.

Don’t replace or overhaul fuel system components before making sure everything is clean and correct. Lycoming has found that contamination of the fuel system is a leading cause of substandard engine operation. Follow the instructions in service instruction 1275 and, whatever solvent or cleaner you use, make sure you apply it for the time that is recommended in the publication. Again, do not take any shortcuts. They could lead to unnecessary repair or replacement of the fuel system.

Instrument Calibration

Keep the Entire Engine Instrumentation System In Calibration

Don’t make adjustments to the engine (oil pressure, fuel pressure, etc.) or attempt to correct high or low oil temperature issues without verifying that the instrumentation is reading correctly. The Lycoming factory has a room that is impervious to vibration and loud outside noises. This is where all our gauges are taken for calibration on a regular basis. Our ability to build every engine to the highest standards relies on knowing exactly what those standards are and more importantly, when we have reached them: every pre-torque, torque, gap and tolerance. It’s the same with an engine in the field. You will do the best job you can when you know you are getting accurate readings from the engine instrumentation.

Brian Costello is a Field Service Engineer for Lycoming. He is a frequent speaker at HAI’s annual Heli-Expo and is also the owner and operator of a 1949 Piper Clipper with a Lycoming O-290-D2 engine.